John Samore

Blog: Lawyer’s Insight on

Legal Matters:

- Thoughts about the law -

"Lawyer's Insight' is a periodic blog by Mr. Samore on

current legal issues that informs readers how current, legal

events influence Americans' lives. If you would like to ask

Mr. Samore to address a particular concern which you may

have, simply send an email to the address at left with

subject "Questions for Lawyer's Insight."

Click on the links below to quickly reach a particular topic,

or just scroll down to read what is of interest. Other

sources of information from Mr. Samore are on the

Common Questions and About Us pages of this website.

If you don’t see a link to a topic of interest, check the other Lawyer’s Insight pages.

Thoughts about the law

• What do you think of all the lawyer advertising? • Analysis: NM still tops in nation for reliance on private prisons • Why Small Crimes are Good for Big Business • Reel to Real: Lawyer Movies That Could Haunt or Help YouWHY SMALL CRIMES ARE GOOD FOR BIG BUSINESS

Article images reprinted with permission. The articles attached to these comments is written by a dedicated journalist, who is highly-respected because he so thoroughly researches all his work before it is published. Crime can be a serious problem but, in this country over the last 35 years, the far worse problem is actually businesses that owe their existence to locking up small-time offenders for long prison sentences. Let me give you a brief overview. In the mid-1980's, laws were passed for the first time that permitted private corporations to operate prisons in which persons convicted of federal or state crimes could serve their sentence. In the same year, with the support of the same Senators (who received their financial contributions from the corporations), Congress passed the sentencing guidelines that greatly restricted the discretion of judges in making sentencing decisions. The reason Congresspeople gave for establishing these guidelines was to be "tough on crime" and make sure people committing similar crimes received similar sentences, but that was not the real reason then, and it still is not the real reason now. These guidelines set prison sentences for non-violent crimes absurdly high in term of incarceration, often with what is called "mandatory minimums." People who became addicted to illegal drugs could not maintain regular jobs, so they would sell or trade illegal drugs to other addicts on behalf of their supplier. This approach virtually guarantees that the low-level sellers (called "low-hanging fruit") got arrested far more than any really important supplier. These low-level addicts need treatment far more than incarceration. Politicians and too many in law enforcement could care less. (Unfortunately, judges become like any other politician when it comes to getting elected or selected.) No one gets elected because they say they want to reduce prison sentences to give non-violent people a chance to get their lives together. They get attention (and elected) by telling hopeful voters that they will be "tough on crime." Now, what does that glib phrase really mean? To simple-minded voters, it can only mean longer and longer prison sentences for people (usually poor) who are convicted. The rest of the Western democracies (Canada, Europe, Scandinavia, most of South America, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, etc.) have far lower rates of incarcerating people who commit crimes. But not us Americans; we think that we must slam people away for years just to get them out of our sight, and then delude ourselves into believing the problem will diminish. A little over ten years ago, Peru decided to try something else, quit locking up drug addicts for minor crimes and committed the their country to funding treatment instead of prison. Within this amazingly short period of time, they have reduced addiction rates over ninety percent (!) and find treatment costs their country far less than imprisoning people. That won't work in good old USA. Why? Because we have hugely-profitable private prison corporations that lock people up to feed profit to their shareholders, and these corporations have far more money to influence legislators with their contributions than those of that stand up for the poor, weak, and convicted people. When you read Jeff Proctor's first article and second article, you will see how outrageous the situation has become. Our office is representing two of the more than 100 people who were ensnared is this outrageous operation in the Albuquerque area last year. The operation was guided by DEA (and others) that wants to convince people that they are doing something to make society better but they really are not. Most of the agents who came to town to set up these powerless addicts had done the same kind of thing in Chicago and two other cites, where they destroy so many lives that were already struggling to escape addiction. Many Americans are considering whether our drug penalties are too harsh and whether there may be a better way. DEA agents with whom I have had this discussion and asked, "How can you do this to these people, running them into prison for such small drug amounts?' They respond, "Change the laws, and we will change the way we act." Maybe they are right, maybe it is that simple. With an Attorney General like Jeff Sessions, who has told his Department of Justice lawyers to be even more severe on small-time drug sales, the likelihood of change for the better is increasingly slim. As a result, we will all be less secure, not more so. Together, we need to ponder how we can change the laws to be more sensible and humane.Reel to Real: Lawyer Movies That Could Haunt or Help You

Reprinted from Spring 2015 NMCDLA Newsletter John Samore, Samore Law, Albuquerque Legal proceedings have long been the source of dramatic tension in film, television, and theater. These art forms profoundly shape public perceptions of our profession and our clients. In turn, they are carried by jurors into deliberation, and even affect the legislators who determine public financing of indigent defense. It behooves us to be aware of popular cultural influences in our efforts to protect the rights and salvage the lives of our clients. Reel to Real will examine some "lawyer movies" that have influenced impressions of defense attorneys and the justice system at work. With references to a famous scene or character, images that have become bigger than life through popular culture, we can gain helpful insight into, and persuasion with, jury panels and official decision-makers. Movies are also a vivid way to illustrate, in mentoring younger colleagues. "Better Ask Saul" is a prime, local example. The new hit AMC series has already received rave reviews and may be destined for a long run with wide viewership. Set in Albuquerque, the star is a hustler-attorney and, as we laugh or shake our heads at his shenanigans, we also cannot help but wince. When we represent our client, will we be seen as cut from the Jimmy McGill cloth? How do we actually see ourselves, individually and as a group? Measure the damage when the long-running series "Law and Order" starts every show by telling its loyal audience that "the criminal justice system is made up of three" elements: the police, the prosecutors, and the victims. Could any other element of justice possibly be missing here? How does such nonsense increase our challenges? (As a wiser colleague than I once said, "Most jurors don't even realize we are bound by the same Code of Ethics as prosecutors.") Ignore these realities at your peril -- and at your client's peril. Do you see yourself an Atticus Finch ("To Kill a Mockingbird"), ethical and honorable, even in defeat? Better check that classic 1962 award-winning film more closely, because Atticus presents (in the climactic trial) one of the more pathetic defenses ever found in fact or fiction (those facial injuries are as likely to have occurred from a backhand blow) and exposes his own coward's morality. When the villain who spit in his face (misdemeanor) is stabbed to death by Boo Radley, Finch quickly accedes to the convenient disposition suggested by the equally weak Sheriff, "Bob Uhl fell on his knife -- let the dead bury the dead." Is this the depth to which we aspire? Maybe you, like Tom Cruise's Lt. Kaffee, think that if he just keeps shouting at the imperturbable, esteemed officer, "I want the truth!" (in lieu of genuine cross-examination), his seasoned witness will suddenly fold completely, give up his career, and admit (paraphrasing here), "Yeah, I guess you got me; I been lyin." Well, that's all he did in the execrable "For a Few Good Men," but it ain't gonna happen in any of our real lives. (Aaron Sorkin, what were you smoking when you wrote this crap?) Maybe a better model is Joe Pesci's streetwise "My Cousin Vinnie," who, for all his shady qualifications and inexperience, puts together a substantive defense on the merits that disproves the prosecution's murder case and carries the day for two innocent men. In the twenty-two years since that surprising gem, few movies have captured what we are supposed to do in a courtroom: follow the rulings (whatever they may be), maintain focus, and find the ethical response. In an entertaining way, it also portrays a misleading admission, how discovery works, judicial discretion, and incisive cross-examination. Might this movie be a good frame of reference for your panel? Remember that the "old movie channel" TCM already has one-third of its audience under thirty-five years of age. Few of our jurors will be of the caliber found in "Twelve Angry Men." While over fifty years old, this famous TV-photoplay-then-movie (better-yet, the more recent, Russian-made "Twelve") is still popular with local playhouses and has been seen by many prospective panelists. Use it to educate. From the perspective of jury dynamics, how do we prevail on men and women who do not know each other or the accused to really care - about the facts, about their duty, about justice? Why does the little guy or gal so often win in fiction to the adulation of the audience in the movie theater, but sitting in the jury box their cheers change to jeers - they cannot wait to lock another one away for "Da Guvmint?" Can becoming conversant with movies help us reach them before it is too late? Trials usually aren't that exciting. Many of our panelists grew up thinking Paul Newman could still win that medical malpractice case ("The Verdict") even after the judge threw out his only expert witness. (Paul's good looks must have won over that jury, although we are never told what the appellate court inevitably did with that judgment.) Many also expect lawyers to continually scream and interrupt each other as they do in "Witness for the Prosecution," "Judgment at Nuremberg," "For a Few Good Men," and so many others of more recent vintage. How do we prepare jurors for the possibility - the inevitability, even - of being bored, while fulfilling their civic duty to listen to the evidence? Better, how do we hone our examinations and arguments so they are compelling and effective? Popular film will not be the sine qua non of effective jury selection, but it is one of the topics that usually makes panel members more comfortable, thus helping you establish rapport and elicit more candid answers. (It is especially helpful if you have a judge who permits rare supplemental juror questionnaires or individual voir dire.) Remind jurors that the issues before them won't be decided in less than two hours - a real trial has no trailer, no review, no plot summaries. They are going to have the responsibility to decide who is the hero, or if there even are heroes and villains. Begin in your voir dire to weave your client and his accusers into a memorable construct that may have helpful artistic references. It can be as simple as asking for hands as to who saw a movie which has poignant similarities. Where will their initial sympathies lie? Are you the big-city boy before a small-town jury (or vice versa)? What movie cops became so zealous (or corrupt) that they tried to convict the innocent ("Les Miserables," et al.), and what other cops have been honorable enough to admit their mistake? What expert just forgot an important part of the puzzle, which led to a mistaken opinion (and an acquittal in "My Cousin Vinnie")? What prosecutor hid the evidence, and which one did the right thing? Trial drama has long been the wellspring of emotion and corruption, deception and redemption, triumph and tragedy. We can and must be aware of the vivid images from popular culture that color jurors' thinking before they walk into the courtroom, and be able to incorporate those images - translate them into real life - for the betterment of our career and the fate of our clients. Next time, we shall look at law-related documentaries and how they can help us be better lawyers.

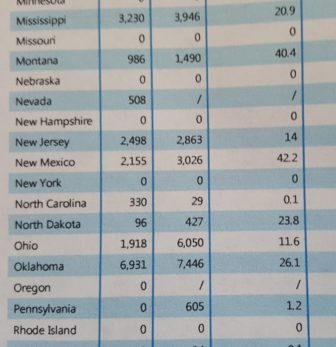

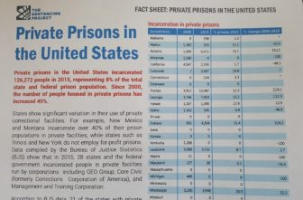

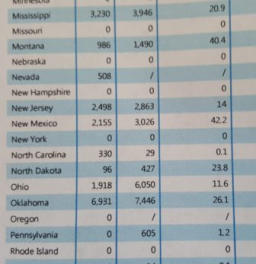

Analysis: NM still tops in nation for reliance on private prisons

By Jeff Proctor, New Mexico In Depth August 29, 2017 Reprinted with permission. New Mexico incarcerates a higher percentage of inmates in privately run, for- profit prisons than any other state, according to a new analysis from the Sentencing Project. It’s a designation New Mexico has held for many years. More than 42 percent of people imprisoned here were being held in one of the state’s five private prisons at the end of 2015, according to the analysis, which is based on figures from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Three of those prisons are operated by GEO Group, Inc.; Core Civic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America) and Management and Training Corporation each run a prison in New Mexico as well. The rest of the New Mexico’s inmates are housed in six government-run prisons. Montana (40.4 percent) was the only other state to top the 40 percent threshold, according to the analysis. Just six states (Hawaii, North Dakota, Mississippi and Oklahoma) held 20 percent or more of their inmates in private prisons. The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit group that advocates for reforming prison conditions and sentencing laws, also compared BJS statistics from 2000 and 2015 to examine the change in each state’s reliance on private prisons. In both years, New Mexico was tops in the nation in percentage of inmates incarcerated in private prisons. The state has used for-profit prisons since the 1990s. New Mexico housed 3,026 of its 7,167 inmates in for-profit prisons in 2015. That’s a 40 percent increase since 2000. Some states, such as Arizona (353 percent) saw significantly larger increases during the 15-year period, The Sentencing Project analysis found. Nationally, private prison use has increased by 45 percent from 2000 to 2015, while the country’s overall prison population has jumped 10 percent, according to The Sentencing Project. The analysis comes amid a shift in federal policy around the use of private prisons — and on the heels of a Justice Department Office of the Inspector General report that found for-profit prisons are more dangerous than their state-run counterparts. Under President Barack Obama, the federal Bureau of Prisons was moving away from contracting with private corporations to house federal inmates and, ultimately, phase out the use of private prisons entirely. President Donald Trump’s attorney general, Jeff Sessions, has reversed that policy. It is unclear whether the shift under Obama would have impacted states’ use of private prisons.

New Mexico leads the nation in the percentage of

inmates it incarcerates in private prisons, followed

by Montana, according to an analysis by The

Sentencing Project, a nonprofit group that

advocates for reforming prison conditions and

sentencing laws.

New Mexico incarcerates 42.2 percent of its inmates

in private prisons, according to an analysis by The

Sentencing Project, a nonprofit group that advocates

for reforming prison conditions and sentencing laws.

What do you think of all the Lawyer Advertising?

November 2017 We lawyers probably have three schools of thought regarding your question: • Many attorneys find advertising on TV or newspapers, and sending letters asking to be hired is essential to their getting business and are not bothered by it a all. • Other attorneys are more established, work with well-known firms who tend to rely on corporate and wealthier clients, so they turn up their noses at any such common (and often crass) marketing. • I am of the middle school that can recall the days of old when attorneys said we are a profession and too good to advertise, so there was no lawyer advertising. At the same time, we accept that it is here to stay, for better or worse. Whether it is "better" or "worse" is up to us. When I made New Mexico my home over thirty years ago, this state was like most states and did not permit lawyers to advertise at all. Many people, especially those without college educations or people who worked at what were called "labor" jobs, did not know anyone who even knew a lawyer. Too often it seemed these folks might suffer injuries and not even know how to go about finding a lawyer that might protect them from further injury or get them some cash payment to reimburse them for these losses. The two leaders in marketing lawyers were Ron Bell and Terry Revo. In very different ways, they tried to let people know that they were open for business. Ron used primarily TV commercials that were as memorable for being witty and entertaining as being informative about his abilities as a lawyer. Terry had one of his staff check the City's public record logs for reported auto accidents each day, then, he could send the persons involved a letter, letting them know that he was available to help them recover damages for their injuries. Our State Bar Association was not amused and both these lawyers had to face litigation to stop their marketing efforts. In response, they argued they had a First Amendment right to advertise and that no restrictions by the State Bar Association, despite its control of who was licenses to be attorneys, prevent what they were doing. As it turned out, the situation was resolved by permitting the lawyers to advertise, with the State Bar Association being able to set standards through a committee which included lawyers and judges and members of the public, to ensure that , whatever ads were run, did not overtly promise certain results or mislead the public. What happened to Ron and Terry was interesting. Ron was able to retire early by selling the firm name, and he remained as the public face of the firm to do the TV advertising you can still see today. Terry Revo took his marketing adviser' suggestions and grew his firm but also had considerable success in his active personal injury practice, which included some notable appellate successes that changed state law for the good of all the people. He still practices here. Another early advertiser, Allan Malott, used a series of low-key, animated advertising that developed his practice and he went on to become a respected state District Court Judge. Attorneys around the country copied Malott's creative ads and paid a pretty penny. Nationally, lawyer advertising has gone over the top. If you get on the Internet, you can now find some truly hilarious ads from lawyers in various states that make you laugh but also makes me wonder what kind of person would want clownish cutups to represent them in any important personal matter. Another phase was heavy advertising in the yellow pages which really was "heavy;" remember those phone books that were so heavy you needed two defensive linemen to lift it off the floor (where you were using it as a doorstop). Today, it is primarily Internet; we live in the day of Google. The techniques of these early pioneers in New Mexico marketing are now overwhelmed by what his done to market lawyers these days. Dozens of lawyers send a staff person to the police station to find out who has been in a car accident or who has been charged with a crime. the lawyer, then, shamelessly sends off a form letter or even calls these people to encourage them to come in for a so-called "free consultation" or whatever little perk they can throw at the person. They put on ads at all hours of day and night, publish little newsletters where they do not just offer simple legal advice but tell readers about their favorite new restaurant, a movie they have seen, or reminisce about their high school days. Who really cares? I kid you not. What in heaven's name any of this nonsense has to do with serving clients, I really have no idea. Almost all of our clients at John Samore Law Office come from referrals by former clients or from referrals by other attorneys. That is all just fine but not the end of the story in this day of The Web. The fact is that at least some advertising for all professionals is here to stay. Whether you are a doctor, diamond-cutter, or lawyer, you have a responsibility to keep your name out there to reach members of the public who are unfamiliar with your work. I do not like to advertise at all. Because this office will never solicit clients in some of these aggressive and intrusive ways, we still need to have what is called an "Internet presence," meaning at least let folks know that your office is taking new clients and still enjoying the practice of law. You do not need a referral to meet with me and discuss your personal situation. Your call or email is always welcome, and, remember, I am ALWAYS the one who calls you back or answers your email. I try to answer every call, not farm you to some staffer. We have found that the personal touch is still special and what people really do not find anywhere else. We are going to chase you; we shall make time for you. This office is here for you, the client, friends of the client, and the client's family.

Blog: Lawyer’s Insight on

Legal Matters:

- Thoughts about the law -

"Lawyer's Insight' is a periodic blog by Mr. Samore

on current legal issues that informs readers how

current, legal events influence Americans' lives. If

you would like to ask Mr.

Samore to address a particular

concern which you may have,

simply send an email to the

address at left with subject

"Questions for Lawyer's

Insight."

Click on the links below to

quickly reach a particular

topic, or just scroll down to read what is of interest.

Other sources of information from Mr. Samore are

on the Common Questions and About Us pages of

this website.

If you don’t see a link to a topic of interest, check

the other Lawyer’s Insight pages.

Thoughts about the law

• What do you think of all the lawyer advertising? • Analysis: NM still tops in nation for reliance on private prisons • Why Small Crimes are Good for Big Business • Reel to Real: Lawyer Movies That Could Haunt or Help YouWHY SMALL CRIMES ARE GOOD FOR BIG BUSINESS

Article images reprinted with permission. The articles attached to these comments is written by a dedicated journalist, who is highly-respected because he so thoroughly researches all his work before it is published. Crime can be a serious problem but, in this country over the last 35 years, the far worse problem is actually businesses that owe their existence to locking up small-time offenders for long prison sentences. Let me give you a brief overview. In the mid-1980's, laws were passed for the first time that permitted private corporations to operate prisons in which persons convicted of federal or state crimes could serve their sentence. In the same year, with the support of the same Senators (who received their financial contributions from the corporations), Congress passed the sentencing guidelines that greatly restricted the discretion of judges in making sentencing decisions. The reason Congresspeople gave for establishing these guidelines was to be "tough on crime" and make sure people committing similar crimes received similar sentences, but that was not the real reason then, and it still is not the real reason now. These guidelines set prison sentences for non- violent crimes absurdly high in term of incarceration, often with what is called "mandatory minimums." People who became addicted to illegal drugs could not maintain regular jobs, so they would sell or trade illegal drugs to other addicts on behalf of their supplier. This approach virtually guarantees that the low-level sellers (called "low- hanging fruit") got arrested far more than any really important supplier. These low-level addicts need treatment far more than incarceration. Politicians and too many in law enforcement could care less. (Unfortunately, judges become like any other politician when it comes to getting elected or selected.) No one gets elected because they say they want to reduce prison sentences to give non-violent people a chance to get their lives together. They get attention (and elected) by telling hopeful voters that they will be "tough on crime." Now, what does that glib phrase really mean? To simple-minded voters, it can only mean longer and longer prison sentences for people (usually poor) who are convicted. The rest of the Western democracies (Canada, Europe, Scandinavia, most of South America, New Zealand, Australia, Japan, etc.) have far lower rates of incarcerating people who commit crimes. But not us Americans; we think that we must slam people away for years just to get them out of our sight, and then delude ourselves into believing the problem will diminish. A little over ten years ago, Peru decided to try something else, quit locking up drug addicts for minor crimes and committed the their country to funding treatment instead of prison. Within this amazingly short period of time, they have reduced addiction rates over ninety percent (!) and find treatment costs their country far less than imprisoning people. That won't work in good old USA. Why? Because we have hugely-profitable private prison corporations that lock people up to feed profit to their shareholders, and these corporations have far more money to influence legislators with their contributions than those of that stand up for the poor, weak, and convicted people. When you read Jeff Proctor's first article and second article, you will see how outrageous the situation has become. Our office is representing two of the more than 100 people who were ensnared is this outrageous operation in the Albuquerque area last year. The operation was guided by DEA (and others) that wants to convince people that they are doing something to make society better but they really are not. Most of the agents who came to town to set up these powerless addicts had done the same kind of thing in Chicago and two other cites, where they destroy so many lives that were already struggling to escape addiction. Many Americans are considering whether our drug penalties are too harsh and whether there may be a better way. DEA agents with whom I have had this discussion and asked, "How can you do this to these people, running them into prison for such small drug amounts?' They respond, "Change the laws, and we will change the way we act." Maybe they are right, maybe it is that simple. With an Attorney General like Jeff Sessions, who has told his Department of Justice lawyers to be even more severe on small-time drug sales, the likelihood of change for the better is increasingly slim. As a result, we will all be less secure, not more so. Together, we need to ponder how we can change the laws to be more sensible and humane.Reel to Real: Lawyer Movies That Could Haunt or Help You

Reprinted from Spring 2015 NMCDLA Newsletter John Samore, Samore Law, Albuquerque Legal proceedings have long been the source of dramatic tension in film, television, and theater. These art forms profoundly shape public perceptions of our profession and our clients. In turn, they are carried by jurors into deliberation, and even affect the legislators who determine public financing of indigent defense. It behooves us to be aware of popular cultural influences in our efforts to protect the rights and salvage the lives of our clients. Reel to Real will examine some "lawyer movies" that have influenced impressions of defense attorneys and the justice system at work. With references to a famous scene or character, images that have become bigger than life through popular culture, we can gain helpful insight into, and persuasion with, jury panels and official decision-makers. Movies are also a vivid way to illustrate, in mentoring younger colleagues. "Better Ask Saul" is a prime, local example. The new hit AMC series has already received rave reviews and may be destined for a long run with wide viewership. Set in Albuquerque, the star is a hustler-attorney and, as we laugh or shake our heads at his shenanigans, we also cannot help but wince. When we represent our client, will we be seen as cut from the Jimmy McGill cloth? How do we actually see ourselves, individually and as a group? Measure the damage when the long-running series "Law and Order" starts every show by telling its loyal audience that "the criminal justice system is made up of three" elements: the police, the prosecutors, and the victims. Could any other element of justice possibly be missing here? How does such nonsense increase our challenges? (As a wiser colleague than I once said, "Most jurors don't even realize we are bound by the same Code of Ethics as prosecutors.") Ignore these realities at your peril -- and at your client's peril. Do you see yourself an Atticus Finch ("To Kill a Mockingbird"), ethical and honorable, even in defeat? Better check that classic 1962 award- winning film more closely, because Atticus presents (in the climactic trial) one of the more pathetic defenses ever found in fact or fiction (those facial injuries are as likely to have occurred from a backhand blow) and exposes his own coward's morality. When the villain who spit in his face (misdemeanor) is stabbed to death by Boo Radley, Finch quickly accedes to the convenient disposition suggested by the equally weak Sheriff, "Bob Uhl fell on his knife -- let the dead bury the dead." Is this the depth to which we aspire? Maybe you, like Tom Cruise's Lt. Kaffee, think that if he just keeps shouting at the imperturbable, esteemed officer, "I want the truth!" (in lieu of genuine cross-examination), his seasoned witness will suddenly fold completely, give up his career, and admit (paraphrasing here), "Yeah, I guess you got me; I been lyin." Well, that's all he did in the execrable "For a Few Good Men," but it ain't gonna happen in any of our real lives. (Aaron Sorkin, what were you smoking when you wrote this crap?) Maybe a better model is Joe Pesci's streetwise "My Cousin Vinnie," who, for all his shady qualifications and inexperience, puts together a substantive defense on the merits that disproves the prosecution's murder case and carries the day for two innocent men. In the twenty-two years since that surprising gem, few movies have captured what we are supposed to do in a courtroom: follow the rulings (whatever they may be), maintain focus, and find the ethical response. In an entertaining way, it also portrays a misleading admission, how discovery works, judicial discretion, and incisive cross-examination. Might this movie be a good frame of reference for your panel? Remember that the "old movie channel" TCM already has one-third of its audience under thirty- five years of age. Few of our jurors will be of the caliber found in "Twelve Angry Men." While over fifty years old, this famous TV-photoplay-then- movie (better-yet, the more recent, Russian-made "Twelve") is still popular with local playhouses and has been seen by many prospective panelists. Use it to educate. From the perspective of jury dynamics, how do we prevail on men and women who do not know each other or the accused to really care - about the facts, about their duty, about justice? Why does the little guy or gal so often win in fiction to the adulation of the audience in the movie theater, but sitting in the jury box their cheers change to jeers - they cannot wait to lock another one away for "Da Guvmint?" Can becoming conversant with movies help us reach them before it is too late? Trials usually aren't that exciting. Many of our panelists grew up thinking Paul Newman could still win that medical malpractice case ("The Verdict") even after the judge threw out his only expert witness. (Paul's good looks must have won over that jury, although we are never told what the appellate court inevitably did with that judgment.) Many also expect lawyers to continually scream and interrupt each other as they do in "Witness for the Prosecution," "Judgment at Nuremberg," "For a Few Good Men," and so many others of more recent vintage. How do we prepare jurors for the possibility - the inevitability, even - of being bored, while fulfilling their civic duty to listen to the evidence? Better, how do we hone our examinations and arguments so they are compelling and effective? Popular film will not be the sine qua non of effective jury selection, but it is one of the topics that usually makes panel members more comfortable, thus helping you establish rapport and elicit more candid answers. (It is especially helpful if you have a judge who permits rare supplemental juror questionnaires or individual voir dire.) Remind jurors that the issues before them won't be decided in less than two hours - a real trial has no trailer, no review, no plot summaries. They are going to have the responsibility to decide who is the hero, or if there even are heroes and villains. Begin in your voir dire to weave your client and his accusers into a memorable construct that may have helpful artistic references. It can be as simple as asking for hands as to who saw a movie which has poignant similarities. Where will their initial sympathies lie? Are you the big-city boy before a small-town jury (or vice versa)? What movie cops became so zealous (or corrupt) that they tried to convict the innocent ("Les Miserables," et al.), and what other cops have been honorable enough to admit their mistake? What expert just forgot an important part of the puzzle, which led to a mistaken opinion (and an acquittal in "My Cousin Vinnie")? What prosecutor hid the evidence, and which one did the right thing? Trial drama has long been the wellspring of emotion and corruption, deception and redemption, triumph and tragedy. We can and must be aware of the vivid images from popular culture that color jurors' thinking before they walk into the courtroom, and be able to incorporate those images - translate them into real life - for the betterment of our career and the fate of our clients. Next time, we shall look at law-related documentaries and how they can help us be better lawyers.

Analysis: NM still tops in nation for reliance on private

prisons

By Jeff Proctor, New Mexico In Depth August 29, 2017 Reprinted with permission. New Mexico incarcerates a higher percentage of inmates in privately run, for-profit prisons than any other state, according to a new analysis from the Sentencing Project. It’s a designation New Mexico has held for many years. More than 42 percent of people imprisoned here were being held in one of the state’s five private prisons at the end of 2015, according to the analysis, which is based on figures from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Three of those prisons are operated by GEO Group, Inc.; Core Civic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America) and Management and Training Corporation each run a prison in New Mexico as well. The rest of the New Mexico’s inmates are housed in six government-run prisons. Montana (40.4 percent) was the only other state to top the 40 percent threshold, according to the analysis. Just six states (Hawaii, North Dakota, Mississippi and Oklahoma) held 20 percent or more of their inmates in private prisons. The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit group that advocates for reforming prison conditions and sentencing laws, also compared BJS statistics from 2000 and 2015 to examine the change in each state’s reliance on private prisons. In both years, New Mexico was tops in the nation in percentage of inmates incarcerated in private prisons. The state has used for-profit prisons since the 1990s. New Mexico housed 3,026 of its 7,167 inmates in for-profit prisons in 2015. That’s a 40 percent increase since 2000. Some states, such as Arizona (353 percent) saw significantly larger increases during the 15-year period, The Sentencing Project analysis found. Nationally, private prison use has increased by 45 percent from 2000 to 2015, while the country’s overall prison population has jumped 10 percent, according to The Sentencing Project. The analysis comes amid a shift in federal policy around the use of private prisons — and on the heels of a Justice Department Office of the Inspector General report that found for-profit prisons are more dangerous than their state-run counterparts. Under President Barack Obama, the federal Bureau of Prisons was moving away from contracting with private corporations to house federal inmates and, ultimately, phase out the use of private prisons entirely. President Donald Trump’s attorney general, Jeff Sessions, has reversed that policy. It is unclear whether the shift under Obama would have impacted states’ use of private prisons.

New Mexico leads the nation in the percentage of

inmates it incarcerates in private prisons, followed

by Montana, according to an analysis by The

Sentencing Project, a nonprofit group that

advocates for reforming prison conditions and

sentencing laws.

New Mexico incarcerates 42.2 percent of

its inmates in private prisons, according to

an analysis by The Sentencing Project, a

nonprofit group that advocates for

reforming prison conditions and sentencing

laws.

What do you think of all the Lawyer Advertising?

November 2017 We lawyers probably have three schools of thought regarding your question: • Many attorneys find advertising on TV or newspapers, and sending letters asking to be hired is essential to their getting business and are not bothered by it a all. • Other attorneys are more established, work with well-known firms who tend to rely on corporate and wealthier clients, so they turn up their noses at any such common (and often crass) marketing. • I am of the middle school that can recall the days of old when attorneys said we are a profession and too good to advertise, so there was no lawyer advertising. At the same time, we accept that it is here to stay, for better or worse. Whether it is "better" or "worse" is up to us. When I made New Mexico my home over thirty years ago, this state was like most states and did not permit lawyers to advertise at all. Many people, especially those without college educations or people who worked at what were called "labor" jobs, did not know anyone who even knew a lawyer. Too often it seemed these folks might suffer injuries and not even know how to go about finding a lawyer that might protect them from further injury or get them some cash payment to reimburse them for these losses. The two leaders in marketing lawyers were Ron Bell and Terry Revo. In very different ways, they tried to let people know that they were open for business. Ron used primarily TV commercials that were as memorable for being witty and entertaining as being informative about his abilities as a lawyer. Terry had one of his staff check the City's public record logs for reported auto accidents each day, then, he could send the persons involved a letter, letting them know that he was available to help them recover damages for their injuries. Our State Bar Association was not amused and both these lawyers had to face litigation to stop their marketing efforts. In response, they argued they had a First Amendment right to advertise and that no restrictions by the State Bar Association, despite its control of who was licenses to be attorneys, prevent what they were doing. As it turned out, the situation was resolved by permitting the lawyers to advertise, with the State Bar Association being able to set standards through a committee which included lawyers and judges and members of the public, to ensure that , whatever ads were run, did not overtly promise certain results or mislead the public. What happened to Ron and Terry was interesting. Ron was able to retire early by selling the firm name, and he remained as the public face of the firm to do the TV advertising you can still see today. Terry Revo took his marketing adviser' suggestions and grew his firm but also had considerable success in his active personal injury practice, which included some notable appellate successes that changed state law for the good of all the people. He still practices here. Another early advertiser, Allan Malott, used a series of low-key, animated advertising that developed his practice and he went on to become a respected state District Court Judge. Attorneys around the country copied Malott's creative ads and paid a pretty penny. Nationally, lawyer advertising has gone over the top. If you get on the Internet, you can now find some truly hilarious ads from lawyers in various states that make you laugh but also makes me wonder what kind of person would want clownish cutups to represent them in any important personal matter. Another phase was heavy advertising in the yellow pages which really was "heavy;" remember those phone books that were so heavy you needed two defensive linemen to lift it off the floor (where you were using it as a doorstop). Today, it is primarily Internet; we live in the day of Google. The techniques of these early pioneers in New Mexico marketing are now overwhelmed by what his done to market lawyers these days. Dozens of lawyers send a staff person to the police station to find out who has been in a car accident or who has been charged with a crime. the lawyer, then, shamelessly sends off a form letter or even calls these people to encourage them to come in for a so-called "free consultation" or whatever little perk they can throw at the person. They put on ads at all hours of day and night, publish little newsletters where they do not just offer simple legal advice but tell readers about their favorite new restaurant, a movie they have seen, or reminisce about their high school days. Who really cares? I kid you not. What in heaven's name any of this nonsense has to do with serving clients, I really have no idea. Almost all of our clients at John Samore Law Office come from referrals by former clients or from referrals by other attorneys. That is all just fine but not the end of the story in this day of The Web. The fact is that at least some advertising for all professionals is here to stay. Whether you are a doctor, diamond-cutter, or lawyer, you have a responsibility to keep your name out there to reach members of the public who are unfamiliar with your work. I do not like to advertise at all. Because this office will never solicit clients in some of these aggressive and intrusive ways, we still need to have what is called an "Internet presence," meaning at least let folks know that your office is taking new clients and still enjoying the practice of law. You do not need a referral to meet with me and discuss your personal situation. Your call or email is always welcome, and, remember, I am ALWAYS the one who calls you back or answers your email. I try to answer every call, not farm you to some staffer. We have found that the personal touch is still special and what people really do not find anywhere else. We are going to chase you; we shall make time for you. This office is here for you, the client, friends of the client, and the client's family.